The Federal Reserve is meeting this week to decide its next step on interest rates just as its yearlong fight against inflation is colliding with a crunch in the financial sector. The Fed’s next move will be closely watched as recent bank failures are stirring memories of the 2008 financial crisis. Even before the central bank policy decision on Wednesday, investors will be looking for more signs of stress in the global banking industry and additional steps from regulators to provide relief. This is a special edition newsletter we’re sending to subscribers of Five Things and New Economy Daily to give an overview of what we’re watching ahead of the meeting.

Will the Fed hike?

There is no shortage of views among investors with expectations shifting between the Fed delivering another quarter-point hike and a pause. The only certainty is that the Fed will refrain from a bigger half-point hike that Chair Jerome Powell had put on the table just before concerns about financial stability emerged. A survey of economists by Bloomberg News shows a median call of a quarter point hike that will take the Fed’s policy rate to a range of 4.75%-5% and the bond market assigns about a 65% chance to that possibility. At the height of bank stress concerns last week, traders lowered the odds of a quarter point hike to less than half while some banks, including Goldman Sachs and Barclays, changed their rate calls and they now don’t expect a rate hike.

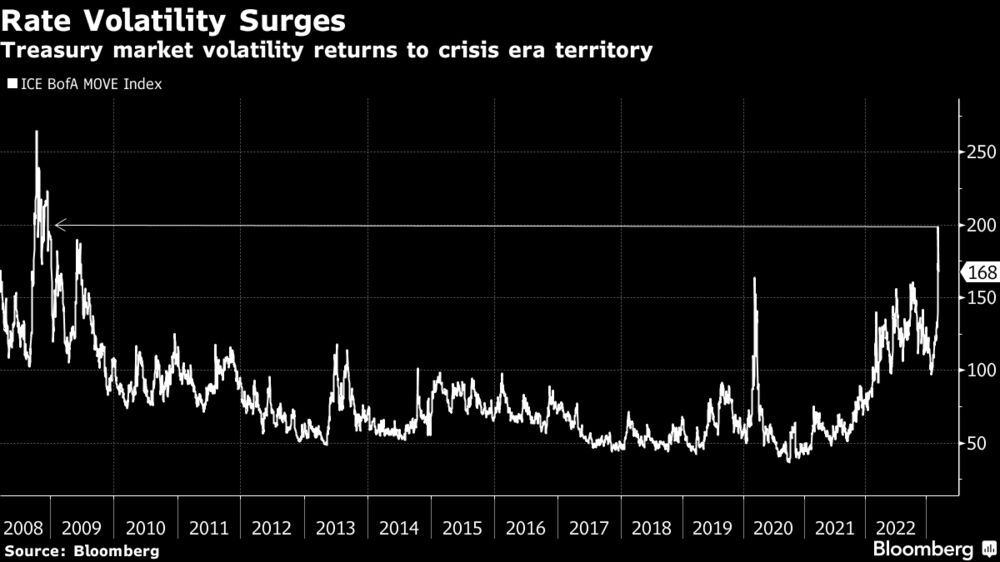

As developments are changing rapidly, amid efforts to support troubled lenders from Credit Suisse to First Republic, rate-hike expectations could shift yet again before Wednesday. The Fed is very unlikely to challenge markets with a surprise move after bond volatility surged to the highest since 2008. Fears of a broader credit crunch and signs of liquidity strains will also be top concerns for policy makers. In the past week, banks scrambling for cash already drew a record amount of funds from the Fed’s emergency facilities, including a new funding backstop, eclipsing a previous record set in the 2008 financial crisis.

“The Fed is handcuffed. “If they hike one more time, it’s one 25 and then pause,” said Jason Bloom, head of fixed income, alternatives, and ETF strategies at Invesco. “It’s time to pause and look at how much damage has been done from tightening.”

Or pause?

An argument for the Fed to pause its rate hikes is that its rapid pace of tightening from near zero in the past year has now broken something in the economy and tightened financial conditions. The Fed had already slowed its pace of rate hikes in December and February and was on a path to eventually stop and assess the cumulative toll of tightening. The trouble is that the US jobs market is still very tight and inflation remains elevated. Stopping now could well prompt a rise in market expectations of inflation and send longer-dated Treasury yields higher on concerns that the Fed is no longer quite so vigilant about price stability. Bloomberg economist Anna Wong reckons that the adverse impact from the bank turmoil is equivalent to no more than one 25-basis point hike by the Fed, meaning that its job isn’t done.

“It would take a durable banking-sector shock to cause the Fed to materially slow rate hikes,” she writes.

A pause now would require the Fed to thread the needle on communicating a clear message to the market that they will resume tightening should data prove resilient. As markets headed to a close on Friday, the idea of the Fed pausing in March, only to resume its hikes in May, should the conditions warrant it, was starting to gain favor among traders. But history shows once the Fed does pause after a series of hikes, the next step is that a rate cut ensues not long after.

What about the dot-plot?

This brings us to the Fed’s latest quarterly update of their various forecasts for the economy and policy rates. Back in December, US officials forecast they would lift rates at a slower pace this year, with their median prediction showing a peak of 5.1% until the end of 2023. That was a clear shot across the bow of a bond market that has been pricing in rate cuts some six months after they expected an eventual Fed pause. This point of difference is a gulf between the central bank and the bond market. Traders now expect the Fed’s policy rate to peak at 4.80%, and by the December meeting, traders see the Fed having cut policy below 4%. That marks a big shift from a market estimate of a 5.7% policy peak and virtually no cuts this year after Powell spoke earlier this month. The market’s pricing of steep rate cuts is “excessive” according to Bloomberg’s Wong, implying losses closer to those seen in the Global Financial Crisis.

Financial stability vs price stability

Clearly the bond market thinks financial stability has become a bigger issue than fighting inflation. That is why all benchmark Treasury bonds from two years to 30 years are now yielding less than 4%, well below the current policy floor of 4.5%. But the Fed’s dilemma between the need to stabilize the financial system and contain inflation is looming large amid signs that relief packages for US banks and troubled Swiss lender Credit Suisse may not be sufficient to stem wider cracks in the industry. In the past week alone, banks tapped the Fed for short-term loans of more than $160 billion and major US lenders provided a $30 billion lifeline to First Republic after the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. The Swiss central bank did the same for Credit Swiss with $54 billion of loans before negotiations began for a sale to UBS. If the Fed indicates confidence in the banks’ ability to access liquidity and deal with deposit flight, it can keep its focus on inflation, which at 6% is still well above its price stability goal of 2%.

While such a stance likely sparks selling pressure in Treasuries, bank stress tends to resonate for a while and credit conditions will tighten appreciably from here. Smaller US banks are important lenders to small and medium sized business, a key driver of employment strength. It may be the case that the resulting slowing in growth and inflation from this kind of tightening in financial conditions allows the Fed to slow or halt its rate hikes after March or May. Another question will be the fate of the central bank’s efforts to contain the size of its $8 trillion balance sheet, which swelled during the pandemic.

Powell’s communication challenge

Once the policy statement and forecasts land, financial markets will focus on just how the Fed chair explains its stance without stirring further concerns — either for financial stability or inflation. This is a very tough job, perhaps more than usual as Powell delivered a hawkish policy outlook just days before a US bank failed. Flip flopping is not a good look for central bankers and does little to boost the Fed’s credibility and stem market volatility. For Powell, the best approach appears one of the Fed delivering a quarter-point hike and nudging up the dot-plot rate forecasts, providing cover in case jobs and inflation data stay hot. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers said on Bloomberg Television Friday that the Fed should not allow “financial dominance” and be spooked into easing its campaign to contain inflation “out of solicitude for the banking system.”

Still, Powell would need to ensure that the Fed and other regulators have done enough to ring fence the banking system so policy officials can keep their focus in inflation and the labor market. For now, markets doubt that is the case and all bets would be off if another financial institution runs into trouble.